“Where We Live NYC:”

The NYC Fair Housing Assessment

In 2018, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) and the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) collaborated with dozens of other government agencies, community-based partners, and consultants to launch “Where We Live NYC.” This initiative was a comprehensive, citywide, participatory fair housing planning process that sought to “study, understand, and address patterns of residential segregation and how these patterns impact New Yorkers’ access to opportunity—including jobs, education, safety, public transit, and positive health outcomes.”[1] Originally, the city embarked on the initiative as a response to a federal mandate that required an extensive assessment of fair housing to qualify for funding from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), but when HUD suspended the mandate, the city decided to proceed with the project anyway.

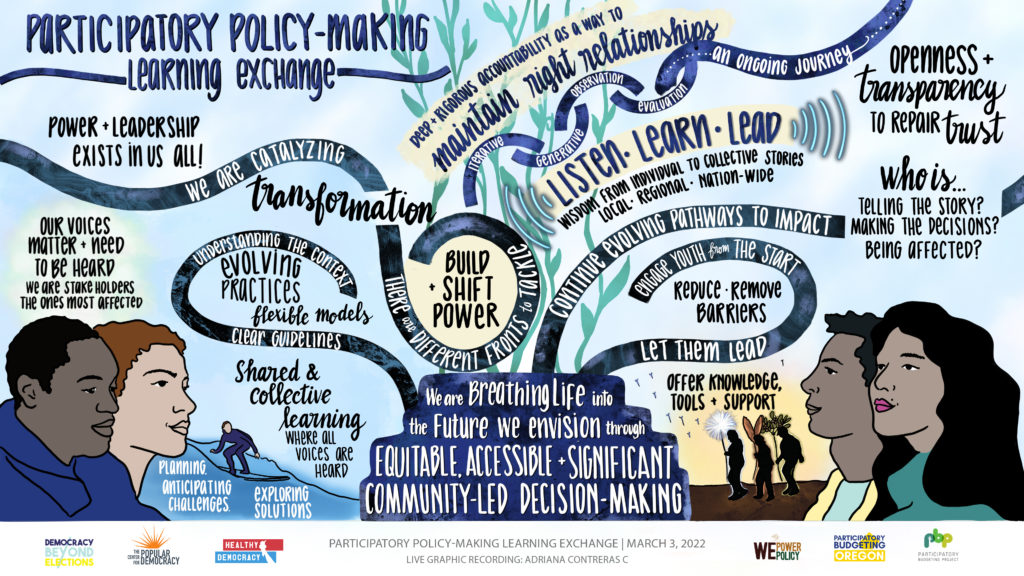

Where We Live NYC was premised on the notion that quantitative data does not tell a complete story and that the lived experiences of New Yorkers provide critical sources of qualitative data that can explain the patterns revealed by quantitative data. Importantly, the city identified that an extensive and inclusive participatory planning process was essential to unearth the on-the-ground impacts of housing segregation and discrimination as well as the motivations of and choices made by residents that quantitative data alone could not. This kind of community/government process not only has important implications for policy recommendations, informed by community experiences, priorities and proposed solutions. It is also an important practice in co-governance, in which communities play an active, decision-making role in the programs and systems that shape their lives.

The Process

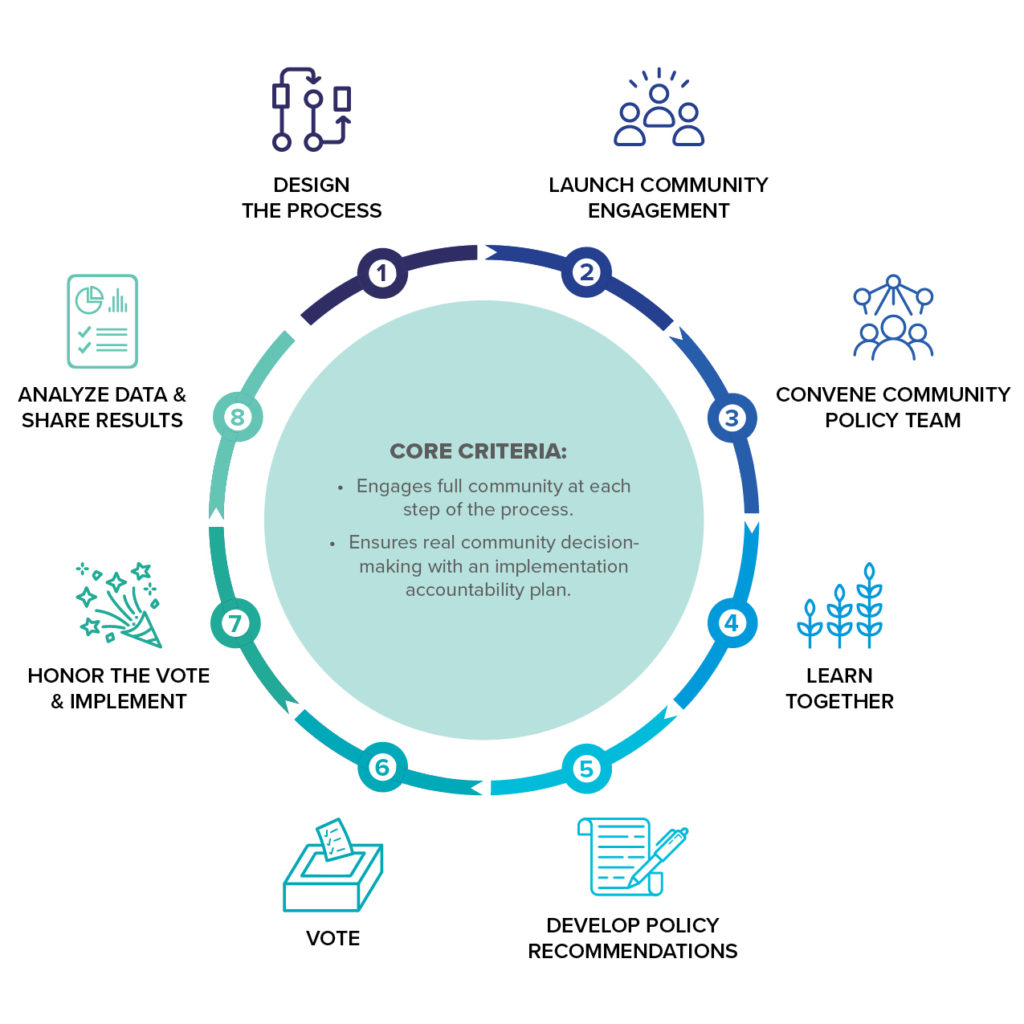

The city partnered with an urban planning, design, and development nonprofit, Hester Street, which developed and implemented a robust, inclusive and equitable community engagement process. Working with Hester Street was critical to the success of the engagement because of their credibility and deep relationships with community-based groups, which government often lacks. The engagement process was a multi-faceted and decentralized approach, which included partnering with 13 trusted community-based organizations (CBOs) that hosted conversations with residents across the five boroughs on topics such as segregation and the legacy of racist policies and practices.[2] To ensure diverse participation, organizers developed a matrix with all of the demographic characteristics of participants that they wanted to recruit, which also included all protected classes under fair housing law and a geographic overlay to ensure geographic diversity. Hester Street then worked with CBOs to co-design engagement materials (including a video about the history of fair housing in NYC), collect and analyze data to inform the community conversations and to provide technical assistance and facilitation support as they engaged representative participants.

In this decentralized model, the CBOs had the money, training, and materials to engage their community in conversations and were equal partners with Hester Street in co-designing materials that would resonate with community members. These CBOs knew best who to bring into the room and were equipped with all of the tools and information needed to facilitate generative conversations. In all, the community engagement process reached over 700 community residents (a small sample size given the size of the city, but a large-scale effort considering the time and resources required to engage this many residents) through 62 community conversations (or focus groups) conducted in 15 languages. In addition, a stakeholder group of 150 advocates, service providers, housing developers, researchers, and community leaders met throughout the process. Finally, the city hosted a number of public events and a public hearing to gather feedback on a set of preliminary draft goals and strategies. They also launched a set of interactive online tools to engage residents in sharing their stories and ideas for addressing fair housing challenges.[3]

Organizers instituted a number of practices in an effort to facilitate participation and generate productive conversation. For instance, to make participation as accessible as possible, organizers made sure to provide free transportation and food, and also sometimes conducted a raffle to honor participants’ time. Organizers were also deliberate in their efforts to ground conversations and manage expectations of the initiative. They began each session by sharing key information about the history of segregation in a short video presentation to make sure all participants had some minimum grounding before jumping into conversation. They were careful to manage expectations by communicating that not everything that was shared would be addressed through the conversation, but that organizers would document everything that was shared (in an anonymized format) to ensure that no contributions to the conversation would be lost.

The data collected through this intensive process (which included data from the community engagement process as well as an intensive analysis of existing quantitative data), was used to develop policy proposals to promote fair housing and fight discrimination. A public report was submitted to HUD in late 2019, which includes policy commitments on the part of the city that are informed directly by NYC residents, and the city released a report on its progress in early 2020.[4]

Obstacles Overcome

& Lessons Learned

Beyond the report itself, another marker of success was that the process has changed the nature of internal conversations within the NYC government. Specifically, the participatory nature of the process helped more city officials become comfortable with the fact that a truly democratic process might mean there is not always consensus and that findings cannot always be neatly packaged and summarized. The process also began to challenge a common assumption among city officials that the public is incapable of grappling with challenging technical concepts. Finally, the initiative challenged government’s tendency to rely primarily on quantitative data when making decisions.

Organizers and TA providers worked hard to make a strong argument for why a participatory process that prioritizes lived experience does indeed live up to the standards of a rigorous research process and should be taken seriously, but this is an ongoing tension of participatory initiatives within government. Perhaps most importantly, the participatory engagement process served to strengthen relationships among NYC’s citywide network on fair housing, growing their capacity to take on fair housing in the future.

Citations

[1] “Updates,” Where We Live NYC, Accessed January 9, 2020, https://wherewelive.cityofnewyork.us/2018/03/09/hpd-launches-where-we-live-nyc-a-comprehensive-fair-housing-planning-process/

[2] “Where We Live NYC: Fair Housing Together,” Hester Street, Accessed January 9, 2020, https://hesterstreet.org/projects/live-nyc-fair-housing-together

[3] “Where we live NYC: Draft Plan,” the City of New York, January 2020, https://wherewelive.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Where-We-Live-NYC-Draft-Plan.pdf, 46-47.

[4] See: “where we live nyc: Draft Plan,” the City of New York, January 2020, https://wherewelive.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Where-We-Live-NYC-Draft-Plan.pdf.